I’m not a big fan of the phrase “fake news” but there’s certainly a growing problem with social media being overwhelmed by false claims, urban myths and conspiracy theories.

Do Masks Cause Cancer?

This week, I spotted a post on my Instagram feed that had been shared by another blogger. The image was a series of photos of a child, showing how easy it was for a kidnapper to disguise a child who was wearing a MASK.

Something about the post made me stop in my tracks. Maybe it was the random capitalisation of MASK. It felt… hinky.

Like – what is the purpose of this post?

Yes, kidnapping, child exploitations and trafficking are BAD. But this post doesn’t help anyone, it just scares them. Let’s look at this logically:

- Most kidnapping attempts (90%) are unsuccessful, and those that are successful typically (75%) involve teenage girls. The scenario depicted here, of a small child being grabbed in a public place, is incredibly rare, and very unlikely to succeed.

- There are obviously no stats yet to show whether kidnapping attempts have increased since lockdown started and masks were introduced. But common sense would suggest that since we’re not having big public gatherings, the opportunity to snatch a child, unnoticed, are pretty limited.

- If we look at a country like Japan, where masks are worn routinely, their kidnapping rate (0.2 per 100,000 population) is 30 times lower than the rate in the UK, where masks haven’t been widely worn.

The scenario identified in this picture? Has almost certainly never happened. It’s ONLY purpose is to scare you into thinking your child is in danger, and sharing it with someone else.

Why would someone post that?

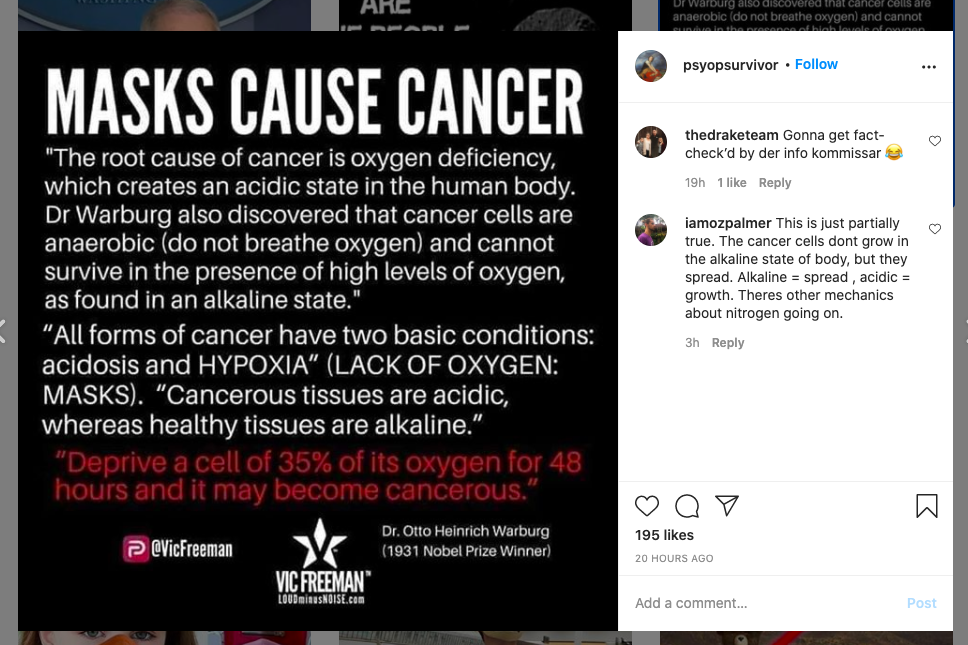

Well, the account that originally posted the image is BONKERS. It’s packed with anti-vaccination, anti-government content. Including this gem claiming that masks cause cancer (see this post on Snopes for a fact-check on this particular bonkers claim):

Why Do We Share Fake News?

The person sharing the kids and kidnapping post didn’t fact check it. I don’t judge her for that. Truthfully, most of us don’t fact check most of the things we share online.

According to Readers Digest, most of us do care about posting things that are true. But we get distracted in the search for new likes, new followers, more engagement.

The mask post did what lots of these channels and pages do very well. It played on emotion.

What sort of mother wouldn’t be affected by a series of scary photos that suggest children are in danger? If I can help just one child by sharing this photo, what harm does it do?

You’ll see similar photos doing the rounds on Facebook and Instagram and WhatsApp. Often they’ll feature some alleged danger to children, or cute animals that have had terrible things happen to them. Perhaps a soldier who’s done something brave. Why wouldn’t any patriot/animal lover/loving parent want to share this?

And Why We Shouldn’t.

The problem with sharing that cute animal photo that has often been published by a far right hate group is this:

Every time we engage with a piece of content on social media, by commenting or liking or sharing, the algorithm is watching. The algorithm sees that engagement as a positive signal, a sign that this piece of content is likely of interest to people like you. And it will then show that content to more people. The next time the page posts, that content is likely to see better reach.

I see this all the time with racist Facebook pages that rely on posting something patriotic, or focusing on kittens, or a heartwarming story about a soldier returning home to their kids, or being denied fair treatment. It’s so easy to click right and not notice the page name is actually “Britain First”. Or anti-vax pages that share positive affirmations about mental wellbeing.

It’s fluffy content designed to seduce us into sharing, liking, commenting – and thereby amplifying voices and furthering the reach of organisations and causes we would never normally lend our support to. By engaging with this content, we are helping these toxic accounts reach more people like us. That’s a problem.

Not to mention that by sharing that fake news, you’re letting the publishers of this page know exactly how to push your buttons next time they want you to engage with them.

This is exactly how Cambridge Analytica targeted undecided voters in the run-up to the Brexit vote. They identified people in crucial areas that might vote either way and they seeded content to try and get older people (who were more likely to be persuaded to vote leave) to engage. Once they’d established that my Mum was a sucker for sharing cute or sad animal stories, they bombarded her with content about how you couldn’t take your dog on holiday unless we left the EU, or how terrible this or that country was because they let small puppies die in the streets.

It’s actually a pretty sophisticated technique that has been used to derail several elections around the world. If you haven’t watched the documentary The Great Hack, then I totally recommend it as an eye-opening, important watch.

Teaching Our Kids to Share with Care

I think as a Mum, I have a responsibility not to share any sort of fake conspiracy nut nonsense online. And I try to show Flea that I challenge it when I see it. Some people will ignore me but mostly if it’s friends, they just haven’t realised what they shared.

I want my teenager to think twice before she shares stuff. And actually, as a child of two journalists, she is GREAT at challenging her friends when they post vaguely racist stats on Snapchat or share “facts” that aren’t attributed to a proper source.

We really need to raise our kids to be intelligent participants in social media conversations. Just as we don’t want our teens to share false rumours in the real world, we don’t want them sharing false information in the online world.

But how do we do that?

How to Avoid Sharing Fake News

- Do share content on topics that matter to you. But share from reputable sources. If something is on the BBC, the NHS, the ONS or similar websites, it’s likely to be pretty credible. Check who posted anything you share.

- Don’t click. Don’t share. Don’t argue. REPORT that content as fake news. Anything else just gives it more legs, and means more people will see it (and potentially believe it).

- If you see a Facebook post, Tweet or newspaper article that is an image with no accompanying link, there’s a good chance it’s been made up in Photoshop. Check the apparent source.

- Don’t assume if something isn’t in the mainstream media it’s a shocking truth we’re trying to hide. It’s more likely been covered and you missed it, OR we fact checked it, and we didn’t post about it because it isn’t true.

- When looking at medical posts, look at where the story comes from. Is it unattributed? Is it from an obscure journal? Medical journals are given an Impact Score between 0 and 60 that shows how credible they are. Google a journal if you want to be sure you’re not sharing something that’s likely not to be trustworthy.

- Get used to using fact checking. Snopes is great for stories about brands, urban legends and conspiracy theories. The BBC also has a great fact checking series called Reality Check. Also in the UK, Full Fact is an independent charity dedicated to fact checking stories doing the rounds in the media and on social media.

Oh wow, it’s scary what people share isn’t it? Equally scary the way people are being targeted politically, I had read that a similar thing happened prior to the general election. It’s great that you are teaching your child to think about this, I think a lot of adults still have a lot to learn about it.

Nat.x

Thanks for this! So important.